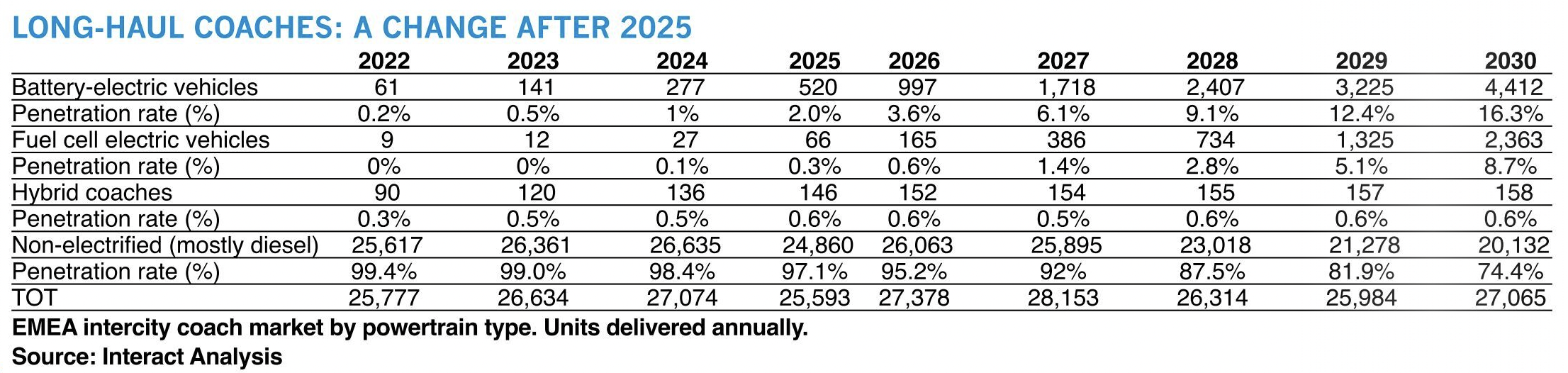

Where diesel isn’t dead yet: 26% of EMEA coaches expected to be electrified in 2030

74% of coaches are estimated to be non-electrified in 2030 in EMEA region. In that segment, for a few years we’ll mostly see plans, targets and pilot projects.

A contribution by Jamie Fox, Interact Analysis, published on May 2022 issue of Sustainable Bus magazine.

74% of coaches are estimated to be non-electrified in 2030 in EMEA region. In that segment, for a few years we’ll mostly see plans, targets and pilot projects.

Electric vehicles have proven themselves with early adopters and will now start to make serious inroads into the market for most vehicle types. This includes cars, urban buses and light and medium duty trucks. These vehicles are electrifying mainly because the total cost of ownership over a number of years is lowest for electric vehicles.

Long-distance coaches hard to electrify

However, as battery electric vehicles sweep much of the on-road commercial market this decade, two applications are going to take longer to crack: long-distance coaches and heavy-duty trucks.

The first of these is coaches, where the main difficulty is the long distance travelled. This requires a larger battery which can makes the up-front cost of the vehicle prohibitively expensive, even if there is an eventual payback period due to fuel savings. A second challenge is very limited supply. Bus manufacturers are focused on urban buses with their electric vehicles, and the supply of intercity battery electric buses is very limited.

Due to the larger market opportunity, electrifying long-haul trucks is attracting interest from OEMs and greater investment in internal research, development and production than long-distance coaches. This is clear from our discussions with OEMs. Components customers are also more focused on the truck market as the larger market. The large number of vehicles in the truck market, and large size of each of these vehicles, means they make a large contribution to emissions that governments increasingly won’t be able to ignore as the decade progresses. This has also contributed to our forecast of decarbonization of long-haul trucks being slightly faster than long haul buses.

There is also an infrastructure challenge. It’s much harder to produce a network of charging stations across a country (what is needed for intercity buses) and much easier to just have one charging hub (as required for urban buses).

No attention from government to long-distance coaches…

Also, governments have given almost no attention, focus or policies towards electrifying intercity buses – which may make some sense as it is a low proportion of total emissions and not as easy to decarbonize as some other areas. In some cases, this is also because governments tend to play a closer role in urban transport systems than they do in long distance buses, perhaps because the free market naturally seems to handle the latter case better than the former. Governments are electrifying urban buses to meet climate goals, whereas private companies have less of an incentive to do so. Finally, air pollution is more of a problem in cities than on intercity routes due to the greater concentration of people. Yet another reason why it makes sense to focus on urban buses first.

Where Western electric coaches do exist, they are often on short routes. For example, Dundee and Edinburgh in Scotland are 60-65 miles apart, and Santiago and Rancagua in Chile are only 55 miles apart. In both cases, the buses do a return trip without charging, allowing operation from a central hub and a similar size battery pack to an urban bus. These coaches, one in Europe and the other in Americas, were provided by Chinese vendors Yutong and King Long respectively. The supply of such buses in the West is extremely limited.

Our interviews with bus OEMs for our upcoming truck and bus report in May led us to conclude that we will see very little improvement in the outlook for intercity bus supply or demand in the short term. Long-distance coaches are forecast to be the last on-road vehicle type to fully decarbonize.

Decarbonization of long-haul trucks to be slightly faster than long haul buses

While the intercity bus market may struggle to attract government attention and private investment due to its small size, the same cannot be said for the market for long haul trucks. To take the example of the US, only an estimated 1,742 intercity buses were registered in 2021 in the US, compared to an estimated 175,583 long haul trucks (this is total vehicles of all powertrain and fuel types).

Where Western electric coaches do exist, they are often on short routes. For example, Dundee and Edinburgh in Scotland are 60-65 miles apart, and Santiago and Rancagua in Chile are only 55 miles apart. In both cases, the buses do a return trip without charging, allowing operation from a central hub and a similar size battery pack to an urban bus. These coaches, one in Europe and the other in Americas, were provided by Chinese vendors Yutong and King Long respectively. The supply of such buses in the West is extremely limited.

Due to the larger market opportunity, electrifying long-haul trucks is attracting interest from OEMs and greater investment in internal research, development and production than long-distance coaches. This is clear from our discussions with OEMs. Components customers are also more focused on the truck market as the larger market.

The large number of vehicles, and large size of each of these vehicles, means they make a large contribution to emissions that governments increasingly won’t be able to ignore as the decade progresses. This has also contributed to our forecast of decarbonization of long-haul trucks being slightly faster than long haul buses.

However, the challenges for electrification of this vehicle type are harder than for any on-road vehicle type. The vehicles are very large and the technology is not very mature. While there is no fundamental obstacle, the best precise architecture (e.g. battery location, type, size, transmission, number of speeds, E-axle or not) is still a matter for debate. Vehicles could not be produced in large volume in 2023 even if there were an unexpectedly high demand.

Infrastructure is another big challenge, especially given that many truckers regularly cross borders requiring the use of different networks with different standards and payment systems. A network with high international compatibility, at least in Europe, will likely make sense but will be another challenge.

Some OEMs are therefore working to a schedule of production beginning to ramp up around 2025 (our country forecasts project most countries to be at between 1% and 3% of long-haul trucks being battery electric in that year), with a third or half of their new vehicles being electrified in 2030. By 2040 we can expect that most or all new on-road trucks will be electrified, either with fuel cells or without. These timescales are already an advance on what OEMs and analysts such as Interact Analysis were forecasting two years ago. The current high prices of raw materials for batteries, and supply chain issues, caused by the pandemic and war in Ukraine provide no incentive to push forward those timescales again.

Long-distance coach electrification will take time

2040 is a long way away. Forecasts for 2040 are quite speculative and there may be technologies, legislation or even changes in public sentiment in 2040 that are impossible to imagine today.

What we can really say with confidence is that diesel will certainly continue to lead – indeed, dominate – in the next few years. The combination of lower price vehicles, existing fuelling infrastructure, available supply and being a known and understood vehicle type give diesel too many advantages for now. And with legislators focusing on city environments where NOX can do more harm, diesel will undoubtedly still account for the largest share of long-haul heavy trucks in 2025. We also forecast diesel will still account for the majority of sales even in 2030, especially when we account for regions like Latin America, Africa, the Middle East and South-East Asia where the pace of electrification is very slow.

In the next few years, for commercial vehicles in urban environments, orders for electric vehicles will start to shift towards purchases in the thousands rather than tens or hundreds. However, for long haul, news will mostly be restricted to plans, targets and pilot projects, showing that there is still some life in the internal combustion engine yet. In some countries with no electrification plans from their government and strong economic growth, it is even plausible that diesel may see a similar number of vehicles sold in 2030 as 2020. Long haul will be the last on-road holdout for diesel, which isn’t ready to die yet.